Georges Benjamin Clemenceau, a name synonymous with unwavering resolve and fierce patriotism, was a towering figure in French history. From his early days as a fiery journalist to his pivotal role as Prime Minister during World War I, Clemenceau's life was a testament to his unwavering principles and relentless pursuit of a strong, republican France.

Born in 1841 in Vendée, a region with a strong republican tradition, Clemenceau was instilled with a sense of independence and a critical eye from a young age. He witnessed the overthrow of the Second French Empire by the Third Republic, a formative experience that shaped his political leanings. Clemenceau pursued a medical degree but found his true calling in journalism. He honed his sharp wit and polemical style, becoming a vocal critic of the newly established republic, which he saw as too conservative.

Driven by a deep republicanism bordering on radicalism, Clemenceau opposed colonialism and championed individual liberty. He was particularly critical of the French role in Algeria, viewing it as an imperialistic venture that undermined republican ideals. This unwavering commitment to his convictions earned him the nickname "Le Tigre" (The Tiger), a moniker that reflected his tenacity and combativeness.

Clemenceau arrives in Paris in October 1861 at the age of twenty accompanied by his father Benjamin, who introduces him to republican circles and his friend Etienne Arago. He moves to the Latin Quarter, where he frequents the cafes and writes a series of political-literary reviews in short-lived journal, Le Travail that attack authors favorable to the government. In 1862, he is imprisoned for 77 days in Mazas prison for having called for protests during the anniversary of the proclamation of the Second Republic. At Mazas, Clemenceau meets political activist Auguste Blanqui, nicknamed « the imprisoned », and becomes a supporter. He defends his medical thesis inspired by positivist thought in 1865 under the direction of Charles Robin.

Georges Clemenceau is a 24-year-old doctor when he moves to the United States in 1865. Remaining for four years, he teaches French, learns English and, like Toqueville before him, discovers American democracy. As foreign correspondent for le Temps, he is a witness to the country’s reconstruction following the Civil War. It was also there that Clemenceau meets Mary Plummer, his wife and the future mother of his children.

Much later, following his retirement from all political activity in January 1920, he publicly voices his concerns that the United States was surrendering to isolationist temptations after failing to ratify the Treaty of Versailles for which President Wilson had so greatly contributed. He returns to the United States without any official mandate in 1922, using a triumphal reception by the authorities and public to call on Americans- firmly, gracefully and as a friend- not to turn their back on the world and to continue serving peace.

POLITICAL FIGHTER

Georges Clemenceau’s long political career begins in republican opposition during the late Second Empire and concludes after the First World War. At each stage– the Paris siege of 1870, mayor of Montmartre at the start of the Commune, deputy for Paris and then the Var, the Panama scandal and exit from parliament, the journalist crusader unwavering in defense of Captain Dreyfus, senator for Var, interior minister, twice President of the Council– Clemenceau stands out as an unrivalled statesman. Loved and admired by some, hated and opposed by others, he never ceases during both peace and war, his often lonely struggle for the republic of his dreams. A man of constant action, he rebels continually against injustice and without compromise (and sometimes without subtlety).

On 18 January 1871, King William I of Prussia is proclaimed Emperor of Germany at Versailles and armistice is signed with the German invader a week later. Georges Clemenceau, mayor of Montmartre and Paris deputy, refuses to accept the annexation of Alsace and Moselle and resigns from the National Assembly. In March 1871, he welcomes the patriotic uprising in Paris, without officially joining the Commune. Again elected deputy for Paris’s 18th district in 1876, Clemenceau breaks with Gambetta and the rest of the government shortly after the republican success in 1877, judging them too cautious in their approach to reform. He campaigns alongside Victor Hugo for amnesty for the Communards. Reelected as deputy on a radical program in 1881, he becomes opposition leader for the extreme left and fights for his vision of a strong and united republic for all citizens.

Actively opposed to colonialization, Clemenceau draws on his eloquence in parliament to bring down successive minsters, including Jules Ferry, his main adversary.

As the 1893 legislative elections approach, Clemenceau is the target of a violent campaign in parliament and the press concerning his close relationship with Cornélius Herz, a swindler implicated in the Panama scandal, who had helped finance his newspaper, La Justice. Clemenceau responds in a notable speech in his electoral district of Salernes, Var where he rejects the attacks and evokes the entirety of his public life and personal integrity. « Where are the millions? », he says. Nevertheless, he is beaten and would remain out of public office for 13 years, instead dedicating himself to making his living as a journalist. Short of funds, he auctions his collections during these years and moves to the modest apartment at rue Franklin.

Clemenceau is a central player from 1897 onwards in the rehabilitation of Captain Dreyfus, who had been unjustly convicted by a military tribunal for spying. Alongside Jean Jaurès and other writers and intellectuals, he fights tirelessly to overturn the judgement. In January 1898, he gives the famous title of J’accuse to Emile Zola’s decisive l’Aurore diatribe against the Army General Staff. Clemenceau would produce no less than 665 articles in various publications until truth and justice prevails. In 1908 and just a few years after Zola’s death, Clemenceau as head of the government arranges for Zola’s ashes to be moved to the Pantheon.

Minister of the Interior (14 March 1906–20 July 1909) – President of the Council (25 October 1906–20 July 1909)

A senator from Var since 1902, Clemenceau is named Minister of the Interior on 13 March 1906. This is his first ministerial title at 65 years of age and he retains the position when he becomes President of the Council just a few months later. The Clemenceau government passes important social legislation covering workers’ pensions, the ten-hour workday and unions. Clemenceau appoints René Viviani as the first Minister of Labor and moderates aspects of the church property inventories required by the 1905 law on the Separation of Church and State. He avoids getting entangled in Moroccan colonialization and favors diplomatic rapprochement with Japan in Asia.

In a bid to modernize the police, he picks Célestin Hennion to head the Surêté Générale police division. Hennion creates specialized regional crime fighting units known as the mobile brigades, implements the latest scientific techniques, introduces automobiles to the police force and equips police officers with a more effective handgun. Clemenceau faces strikes in the north following the Courrières mine disaster and in the southern wine regions.

After attempting negotiations with the strikers and anxious to prevent disorder, Clemenceau repeatedly calls in the troops to control the situation. This alienates the Socialist left led by Jean Jaurès and the verbal battles in parliament between Clemenceau and Jaurès become famous.

However, his Minister of Finance, Joseph Caillaux, was unable to establish an income tax, and he himself had to deal with the leader of the Languedoc winegrowers, Marcellin Albert (1907), following the mutiny of the "soldiers of the 17th".

As a former anti-colonialist, he sent Lyautey to restore order in eastern Morocco, because honor demanded that France not back down. Outside France, his moderate stance helped avoid war. At the time of the Bosnian affair in 1908 (an Austro-Russian conflict almost broke out when Bosnia-Herzegovina was purely and simply annexed by Austria), he let the Russian government know that he would not support it. In 1909, he committed France to the path of peaceful coexistence with Germany (agreement of February 9, 1909 on Morocco), a policy that failed in spite of him.

IN OPPOSITION (1909-1913)

But attacked by Jaurès, with whom he engaged in endless oratorical jousting, discredited by the dismissal of 54 officers following a postal workers' strike (1909), attacked by the Right and the business world, who saw him as the man behind the income tax, Clemenceau was defeated on July 20, 1909: "He died of his superiority", said Barrès. And indeed, not since Jules Ferry, with the exception of Waldeck-Rousseau, had France known such continuity of government and such a statesman.

Returning to the opposition, the "Tiger" successively brought down the Caillaux (1912) and Briand (1913) governments, and fought Poincaré's candidacy for the presidency of the Republic; this was the origin of a famous falling out between the two men.

Faced with the inevitability of war, Clemenceau's Jacobin patriotism was reawakened: he voted for three years' military service and founded the newspaper L'Homme Libre, whose first issue appeared on May 5, 1913.

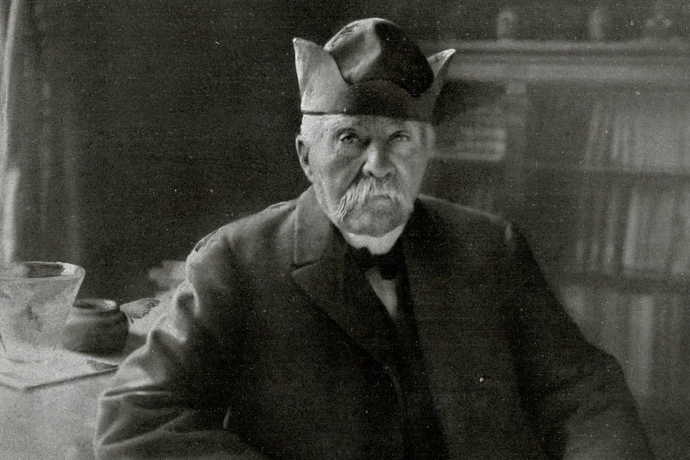

The pettiness of politicians and parliamentary groups, and Poincaré's distrust in particular, delayed the arrival in power of the "Old Man", as the soldiers called him, for three years. During this period, both as head of the Senate Army Commission and in his newspaper, which became L'Homme enchaîné, Clemenceau denounced the inadequacy of the war effort, railed against the creation of fronts in the East, and fiercely controlled the government (during the Battle of Verdun, he forced Briand to appear before the commission eighteen times). He was the "watchdog at the battlements of the nation". With his deformed hat, woollen scarf, grey gloves and cane, he created the legendary figure of the "Father of Victory", immortalized by his statue on the Champs-Élysées in Paris.

With the entry of the United States into the war (April 1917), which Clemenceau had ardently hoped for, 1917 marked a turning point in the conflict, but defeatism swept through both the army and the rear; Russia abandoned the struggle; secret negotiations, in which Aristide Briand took part, aimed to establish a "white peace" (with neither victor nor vanquished). Clemenceau bristled at the prospect. In the Senate, he attacked Louis Malvy (July 22, 1917), who was covering up for the defeatists. "Our goal is to win; to achieve it, we need the courage to choose the path of duty and to go straight ahead. Within a year, Clemenceau would achieve this goal.

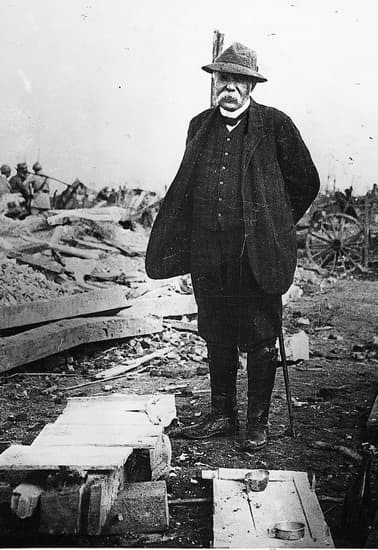

Recalled to the government, at the age of 76, by Poincaré, President of the Republic, who had overcome his personal antipathy, Clemenceau took charge of a war cabinet invested on November 16, 1917. He let the military chiefs act, and stubbornly defended them in the assemblies; but he confined them to their own domain, and jealously maintained the supremacy of civilian power, which he illustrated by frequent visits to the armies. He proclaimed that his only program was to "wage war" until final victory. That's why he had Caillaux and Malvy, avowed supporters of a compromise peace, arrested.

While Pétain re-established morale at the front, Clemenceau launched a 10-billion loan and placed Ferdinand Foch at the forefront: on March 26, 1918, at Doullens, he imposed him as sole commander of the Allied armies just as General Erich Ludendorff launched his decisive offensive on the Somme.

In these tragic circumstances, Clemenceau imbued the whole country with his energy. He ran from one headquarters to another, improvised the Defense Against Aircraft (DCA) in Paris and won the confidence of the House. Thanks to American reinforcements, Foch launched the counter-offensive in Champagne in July 1918.

In 1918 he made a speech that will live long in the memory.

"As for the living, to whom, from this day, we extend our hand and whom we shall welcome, when they pass along our boulevards, on their way to the Arc de Triomphe, may they be greeted in advance! We await them for the great work of social reconstruction. (Loud applause.) Thanks to them, France, yesterday a soldier of God, today a soldier of humanity, will always be a soldier of the ideal! "

On November 11, 1918, the armistice is signed ( armistice de Rethondes). The "Tiger", overcome with emotion, receives the homage of the fatherland from Parliament. His "monarchy" had saved France. Now it's a question of winning the peace.

As the leader of a nation that had been invaded three times in the space of a century, Clemenceau, supported by Marshal Foch, believed that France should annex the Rhineland and the Saar, and extend its borders to the Rhine. This was the revolutionary conception of natural borders as a guarantee of national security. This concept was opposed by Wilsonian idealism (the right of peoples to self-determination) and British realism, concerned not to weaken too much a Germany that could be both a rich economic outlet and a shield against Bolshevism. The Treaty of Versailles was the result of a combination of these different conceptions.

Representing France on the Council of the Big Four (composed of Thomas Woodrow Wilson for the United States, Lloyd George for Great Britain, and Vittorio Orlando for Italy), Clemenceau, president of the Paris Conference, could only obtain a formal guarantee from the Anglo-Saxons against German aggression. Moreover, in 1918, Germany did not consider itself defeated. It expected moderate conditions. It blamed Clemenceau for the exorbitant nature of the treaty, because it was Clemenceau who presented it on behalf of the Allies. Hitler's revenge against France was thus in the making.

On the other hand, public opinion held Clemenceau responsible for France's failure to annex either the Saar or the Rhineland.

His popularity plummeted all the faster as, at home, haunted by the fear of Bolshevism, he broke the strikes of January 1919 and dispersed a demonstration by war widows. Following the unrest of May 1, 1919, he pushed through the eight-hour working week law and the income tax. Paradoxically, the old Jacobin, patronizing Alexandre Millerand's "national bloc", had the most reactionary Chamber of Deputies elected in France since Mac-Mahon.

Clemenceau intended to be "carried" to the presidency of the Republic, but Briand's and Poincaré's grudges, as well as his anticlerical stance on the question of relations with the Vatican, made him prefer Paul Deschanel (January 16, 1920).

Wounded in his pride, ulcerated by the ingratitude shown towards him, the "Tiger" tendered his resignation from his cabinet on January 18; from then on, he refused to return to the political arena.

His last years - as solitary as his whole life had been - were devoted to travel (his 1922 visit to the United States was a triumph), meditation (Au soir de la pensée, 1927) and polemics (Grandeur et misères d'une victoire, 1929). The Académie française had elected him in 1918, but he never held a session.

Why doesn't Clemenceau get the recognition he deserves?

This is just my personal opinion, but in my opinion, Clémenceau is seen as the person most responsible for the severity of the Treaty of Versailles, as written above, as a warmonger, and therefore an "extremist".

Compare this with de Gaulle, who enjoys a positive image. De Gaulle, on the other hand, is seen not only as a savior, but also as the man of reconciliation with Germany. Even if the reality is more complex than that, this is still the image the French have of the great general.

Clemenceau, on the other hand, is seen as the man who would lead us to the abyss in 1940.

Most Helpful Opinions