This may seem a strange topic to write about- on International Women's Day, no less, and especially because I'm a woman. But I've decided to share this with everyone because of an article I saw on The Globe & Mail that was written *for* Women's Day and is so thoroughly misleading that it rubbed me the wrong way.

(the article in question is here.)

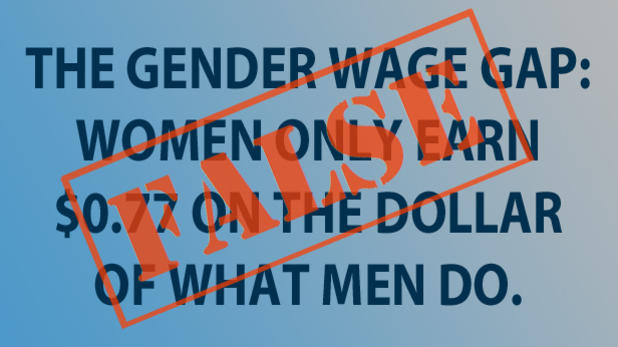

I actually wrote an essay on this exact topic for my intro-level sociology class And, if you've ever taken sociology, political science, or gender studies, then you've probably had the supposed 'gender wage gap' shoved down your throat at some point. In what world does [insert number here] cents equal a dollar? has become the rallying cry of empowered women everywhere... but what most of us don't realize is that calling it a 'gender wage gap' is a misnomer, as well as an oversimplification.

First of all, the 'gender wage gap' is simply the median wage of men minus the median wage of women, expressed as a proportion of the median wage of men (Evans, 2002). It does not account for differences in profession, employment statuses (full-time, part-time, contract or temporary workers, students) or hours worked; it is also well-known that a woman’s career progress is often interrupted by the biological event of maternity and the culturally associated child care (Bodkin & El-Helou, n.d.), which contributes to income inequity between the two genders.

Human capital theory also suggests that women may choose to trade off salary and advancement for other more relational priorities, and that young women continue to choose career priorities that are associated with lower salaries (Schweitzer, Ng, Lyons, & Kuron; 2011). This is likely because these sectors offer greater degrees of flexibility, in the event of a family emergency– if a child or other relative falls ill, it is still widely expected that women, not men, will take responsibility as the notion still exists that women are naturally more instinctive parents and are expected to limit themselves in response via their career choices.

Recent time-budget evidence shows that women continue to bear the major care responsibilities within families and that encouraging longer maternity leave for women and other such practices can “foster horizontal segregation by encouraging women to choose occupations in which patterns of intermittent employment are less likely to be damaging to their career progression (Evans, 2002). Indeed, family days and medical leave are far easier to come by in the retail and service sectors, which are known for their flexibility; Evans (2002) argued that “reductions in working hours for family reasons are also likely to slow advancement in a competitive environment” and that women are more likely than men to engage in either part-time or temporary employment.

That all said, women who focus on their careers instead of families face a host of other challenges. Those who choose to buck social norms by not having children or taking on the role of nurturer are often regarded as cold, selfish, unfeminine… and that is just the start of a long litany of accusations lobbed at those who are child-free by choice. Author Laura Kipnis (2015) explains in her essay, Maternal Instincts, that the sexualized division of labour is a product of the industrial revolution, when it was decided that men would be the providers and women the nurturers. She goes on to debunk several popular myths regarding the titular instinct, as do the other fifteen authors– thirteen women and three men— who contributed to the collection, which was compiled and edited by Meghan Daum. A New York Times review of the anthology echoed that sentiment when its author wrote that “our societal conviction that women are mothers foremost, people second, is so pervasive that the possibility of debunking it can seem its own kind of wish” (Bolick, 2015).

In most industrialized countries, paying someone less based on gender is illegal. The Canadian Human Rights Act (1985) states that “it is a discriminatory practice for an employer to establish or maintain differences in wages between male and female employees employed in the same establishment who are performing work of equal value”, followed by “for greater certainty, sex does not constitute a reasonable factor justifying a difference in wages” and “where the ground of discrimination is pregnancy or child-birth, the discrimination shall be deemed to be on the ground of sex”.

It's no secret that women have to choose between their personal and professional lives, in a way that men don't. So perhaps the bigger issue is outdated gender roles(and the men who love us) respond to them. That's not to take a massive dump on those women who aspire to those things; some people enjoy cooking, cleaning, and raising kids, and that's all fine and well. But perhaps it's time to change how society views those of us who don't.

In conclusion, it is fair to say that, while we have made progress towards income parity (at least here in Canada), we still have some ways to go before antiquated social norms become relics of the past. And, though a wage gap does exist between men and women, it is not due to gender alone that such inequities persist. Still, if there is a company out there that is willing to pay me, a first-year English major and part-time retail clerk, seventy-seven cents for every dollar my professors make in a year, I will gladly accept.

-

Works cited:

Bodkin, Ronald G., & El-Helou, Majed (2001). Gender Differences in the Canadian Economy, with Some Comparisons to the United States (Part II: Earnings, Low Incomes, and the Allocation of Time). Transaction Publishers.

Bolick, Kate (2015). Sunday Review: “Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision Not to Have Kids". New York Times, retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/12/books/review/selfish-shallow-and-self-absorbed-sixteen-writers-on-the-decision-not-to-have-kids.html?_r=0

Daum, Meghan. (Ed.). (2015). Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision Not to Have Kids. New York, NY: Picador.

Evans, John M. (2002). Work/Family Reconciliation, Gender Wage Equity and Occupational Segregation: The Role of Firms and Public Policy. University of Toronto Press.

Schweitzer, Linda, Ng, Eddy, Lyons, Sean, & Kuron, Lisa. (2011). Exploring the Career Pipeline: Gender Differences in Pre-Career Expectations. Relations Industrielles / Industrial Relations, 66(3), 422-444.

The Canadian Human Rights Act, Section 53 (1985-).

Holidays

Holidays  Girl's Behavior

Girl's Behavior  Guy's Behavior

Guy's Behavior  Flirting

Flirting  Dating

Dating  Relationships

Relationships  Fashion & Beauty

Fashion & Beauty  Health & Fitness

Health & Fitness  Marriage & Weddings

Marriage & Weddings  Shopping & Gifts

Shopping & Gifts  Technology & Internet

Technology & Internet  Break Up & Divorce

Break Up & Divorce  Education & Career

Education & Career  Entertainment & Arts

Entertainment & Arts  Family & Friends

Family & Friends  Food & Beverage

Food & Beverage  Hobbies & Leisure

Hobbies & Leisure  Other

Other  Religion & Spirituality

Religion & Spirituality  Society & Politics

Society & Politics  Sports

Sports  Travel

Travel  Trending & News

Trending & News

Most Helpful Opinions