Since Charles Darwin published the theory of evolution by means of natural selection in 1859, myths and misinterpretations have eroded public understanding of his ideas. For example, some people continue to argue that evolution isn't a valid scientific theory because it can't be tested. This, of course, isn't true. Scientists have successfully run numerous laboratory tests that support the major tenets of evolution. And field scientists have been able to use the fossil record to answer important questions about natural selection and how organisms change over time.

Still, the evolution-is-not-falsifiable myth remains popular. So does this one: The second law of thermodynamics, which says an orderly system will always become disorderly, makes evolution impossible. This myth reflects a general misunderstanding of entropy, the term used by physicists to describe randomness or disorder. The second law does state that the total entropy of a closed system can't decrease, but it does allow parts of a system to become more orderly as long as other parts becomes less so. In other words, evolution and the second law of thermodynamics can live together in harmony.

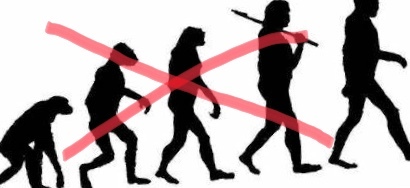

One of the most persistent myths, however, concerns the relationship of humans to great apes, a group of primates that includes the gorilla, orangutan and chimpanzee. Someone who believes the myth will say, "If evolution exists, then humans must be descended directly from apes. Apes must have changed, step by step, into humans." This same person will often follow up with this observation: "If apes 'turned into' humans, then apes should no longer exist." Although there are several ways to attack this assertion, the bottom-line rebuttal is simple -- humans didn't descend from apes. That's not to say humans and apes aren't related, but the relationship can't be traced backward along a direct line of descent, one form morphing into another. It must be traced along two independent lines, far back into time until the two lines merge.

The intersection of the two lines represents something special, what biologists refer to as a common ancestor. This apelike ancestor, which probably lived 5 to 11 million years ago in Africa, gave rise to two distinct lineages, one resulting in hominids -- humanlike species -- and the other resulting in the great ape species living today. Or, to use a family tree analogy, the common ancestor occupied a trunk, which then divided into two branches. Hominids developed along one branch, while the great ape species developed along another branch.

What did this common ancestor look like? Although the fossil record has been stingy with answers, it seems logical that the animal would have possessed features of both humans and apes. In 2007, Japanese scientists believe they found the jawbone and teeth of just such an animal. By studying the size and shape of the teeth, they determined that the ape was gorilla-sized and had an appetite for hard nuts and seeds. They named it Nakalipithecus nakayamai and calculated its age to be 10 million years old. That puts the ape in the right place on the time line. More important, the scientists found the ancient bones in the Samburu Hills of northern Kenya. That puts N. nakayamai in the right geographic place, along a trajectory of hominid evolution that stretches for several hundred miles in eastern Africa. The Middle Awash region of Ethiopia lies to the north, where the African continent dead-ends into the Red Sea.

Awash with Answers

Today, the Middle Awash region burns hot and inhospitable beneath a desert sun. But 10 million years ago, according to paleontologists and geologists, it held a cool, wet forest teeming with life. Is it possible that an apelike creature such as N. nakayamai lived in these fertile woodlands? Is it furthermore possible that the creature was just beginning to experiment with a new lifestyle, one that brought it down to the ground from the trees? Scientists think so, and they've been coming for years to the Middle Awash region, as well as points south, to learn when and how humanlike species diverged from the great apes.

One of the most important Middle Awash discoveries came in 1994, when a team of scientists led by Tim White of the University of California, Berkeley, found skeletal remains that included skull, pelvis and hand and foot bones. When the team pieced the skeleton together, it revealed a very early hominid that walked upright, yet still retained an opposable toe, a trait commonly found in tree-climbing primates. They named the new species Ardipithecus ramidus, or Ardi for short, and determined that it lived 4.4 million years ago. In anthropological circles, Ardi has enjoyed almost as much fame as Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis), the 3.2-million-year-old hominid discovered in 1974 by Donald Johanson in Hadar, Ethiopia.

Lucy was the earliest known human ancestor for years, and for a while it seemed that scientists might never peer any deeper into our dim past. Then Ardi came along and, more recently, other landmark discoveries. In 1997, scientists found the bones of a new species, Ardipithecus kadabba, that lived in the Middle Awash region between 5 and 6 million years ago. And in 2000, Martin Pickford and Brigitte Senut from the College de France and a team from the Community Museums of Kenya unearthed one of the oldest hominids to date. Its official name was Orrorin tugenensis, but the scientists referred to it as Millennium Man. This chimpanzee-sized hominid lived 6 million years ago in the Tugen Hills of Kenya, where it spent time both in the trees and on the ground. While on the ground, it most likely walked upright.

Now scientists are working to close the gap between Millennium Man and the true "missing link" -- the common ancestor that gave rise to humans down one line and great apes down another. Could N. nakayamai be that link, or is there another species in between? The answer, most likely, lies buried in the dry soil of eastern Africa.

One last piece of information is that apes have 48 chromosome and we have 46 chromosomes, therefore that is proof that we did not evolve from apes because then we would have the same amount of chromosomes. Also, if we evolved from apes wouldn't they all have evolved at some point then? Or at least most of them. Over the past few million years we have not seen any proof of this.

Most Helpful Opinions