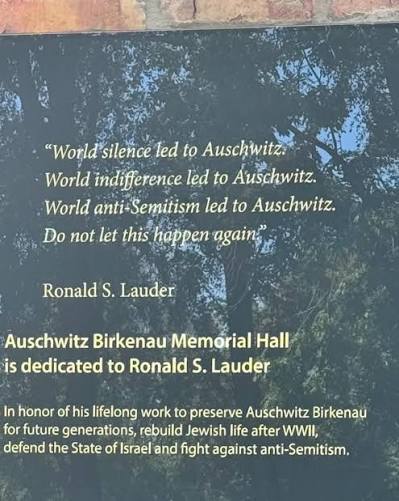

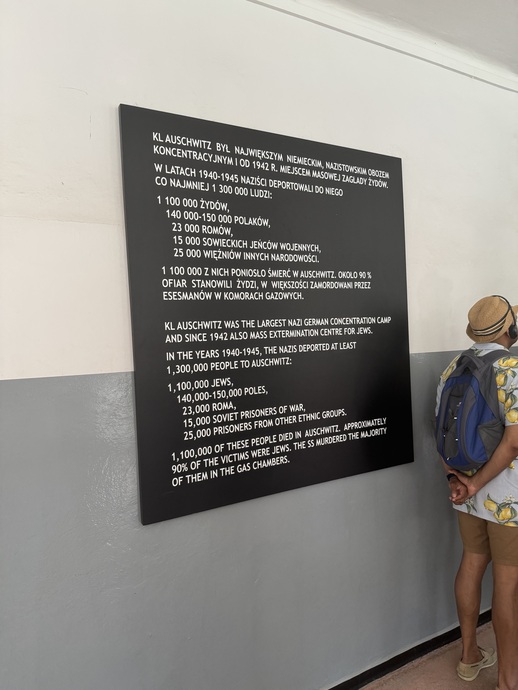

The Holocaust stands as one of the most harrowing chapters in human history, a testament to the depths of cruelty that can arise when societies fail to uphold the sanctity of human life. At the Auschwitz Extermination Camp, a site where over a million people were systematically murdered, a poignant quote by Ronald S. Lauder captures the essence of this tragedy: “World silence led to Auschwitz. World indifference led to Auschwitz. World anti-Semitism led to Auschwitz. Do not let this happen again.” This inscription serves as a stark reminder that the horrors of Auschwitz did not emerge overnight but were the culmination of years of escalating hatred, division, and dehumanization. To understand Auschwitz is to recognize that it did not happen in a vacuum; it was the product of a deliberate process fueled by the disregard for human dignity, the rigid classification of groups into “us versus them,” and the perception of the “other” as an inherent enemy threatening one’s way of life.

The path to Auschwitz began long before the construction of the camp in 1940, rooted in the socio-political turmoil of post-World War I Germany. The Treaty of Versailles imposed harsh reparations and territorial losses on Germany, fostering widespread resentment and economic instability during the Weimar Republic. Into this void stepped the Nazi Party, led by Adolf Hitler, who exploited these grievances by promoting an ideology of racial purity and Aryan supremacy. Anti-Semitism, which had simmered in Europe for centuries, was amplified through propaganda that portrayed Jews as subhuman parasites responsible for Germany’s woes. This disregard for human dignity manifested in laws like the 1935 Nuremberg Laws, which stripped Jews of citizenship and basic rights, institutionalizing discrimination. The “us versus them” mentality was not merely rhetorical; it divided society into insiders, loyal Germans, and outsiders, including Jews, Romani people, disabled individuals, homosexuals, and political dissidents, who were seen as existential threats. This enemy framing justified violence, from the Kristallnacht pogroms of 1938, where synagogues were burned and Jews were attacked, to the eventual Wannsee Conference in 1942, which formalized the “Final Solution” for mass extermination.

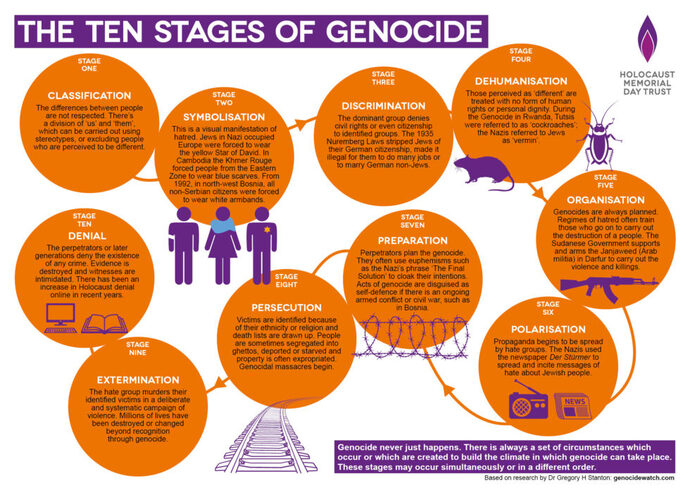

To fully grasp how such atrocities unfold, it is essential to examine genocide as a structured process, as outlined by Gregory Stanton in his model of the ten stages of genocide. 20 These stages illustrate that genocide is rarely spontaneous but builds incrementally, allowing societies to normalize horror. In the Holocaust:

Classification: Societies divide people into categories, such as “Aryan” versus “non-Aryan,” creating binary oppositions that erode shared humanity.

Symbolization: Groups are marked with symbols, like the yellow Star of David forced upon Jews, to visibly reinforce divisions.

Discrimination: Laws and policies exclude targeted groups from society, as seen in the Nuremberg Laws denying Jews equal rights.

Dehumanization: Propaganda equates victims with animals or vermin, Jews were called “rats” or “parasites,” stripping them of empathy and justifying mistreatment.

Organization: State apparatuses, like the SS and Gestapo, are mobilized to plan and execute the agenda.

Polarization: Extremists drive wedges between groups through hate speech and boycotts, isolating victims further.

Preparation: Victims are segregated into ghettos, lists are compiled, and weapons are stockpiled, as occurred in the lead-up to deportations.

Persecution: Property is seized, forced labor imposed, and mass killings begin in earnest, transitioning to camps like Auschwitz.

Extermination: The systematic murder phase, where Auschwitz’s gas chambers and crematoria claimed lives on an industrial scale.

Denial: Perpetrators cover up evidence, and even after the war, some denied the scale of the genocide.

This framework reveals how indifference and silence from the international community, evident in the Evian Conference of 1938, where nations refused to accept Jewish refugees, allowed these stages to progress unchecked. Auschwitz, originally a concentration camp for Polish political prisoners, evolved into a death factory by 1942, embodying the apex of this process.

Imagine, then, a hypothetical future scenario in a prominent democratic nation grappling with rapid social changes and deepening internal divisions. In this country, economic inequalities expand amid technological advancements and shifting demographics, cultivating resentment among various population segments. Political leaders begin classifying citizens along ideological, cultural, or ethnic lines: “loyalists” versus “disruptors,” “insiders” versus “outsiders.” Symbolization follows, with digital icons, emblems, and catchphrases denoting allegiance, while discrimination emerges through regulations limiting civic participation or resources for specific groups. Dehumanizing language from prominent voices brands opponents as “threats” or “invaders,” amplified across communication networks. Organizations arise, including partisan networks and informal alliances, further polarizing the populace through isolated information bubbles that demonize the “other.” Preparation entails assembling records of critics, equipping advocates, and normalizing unofficial enforcement. Persecution intensifies with selective intimidation, compelled displacements, or containment measures framed as “protective actions.” If unaddressed, extermination might not involve explicit facilities but could occur via officially endorsed aggression or deliberate inaction resulting in widespread fatalities. Ultimately, denial would reshape narratives, attributing blame to those affected or rejecting reports as fabrications. In this scenario, the nation drifts toward genocide not via abrupt upheaval but through gradual undermining of principles, where “us versus them” evolves into an inescapable reality.

Yet, such hypotheticals are not mere abstractions; they echo patterns observable in contemporary societies. Consider how, in recent years, divisions have deepened in ways that mirror early genocidal stages. Over the last decade, this unnamed nation has witnessed a surge in political violence, from large-scale riots that disrupted cities and institutions to direct threats against leaders. 11 In 2020, widespread protests over social justice issues turned violent in several instances, with buildings set ablaze and clashes between demonstrators and law enforcement resulting in injuries and deaths. 16 The following year, a mob stormed the national capitol building in an attempt to overturn an election, leading to fatalities and widespread chaos. 12 More alarmingly, assassination attempts on high-profile political figures have escalated, including two separate incidents in 2024 targeting a former president, one at a rally in Pennsylvania and another at a golf course in Florida. 3 Tragically, 2025 brought successful assassinations, such as those of former Minnesota House Speaker Melissa Hortman in June and conservative activist Charlie Kirk in September, intensifying concerns of an escalating cycle of retribution. 8 These events, coupled with over 300 documented cases of political violence since early 2021, highlight a troubling trend where ideological enemies are increasingly seen as existential threats, fostering an environment of fear and retaliation.

In summarizing this exploration, it becomes clear that the Holocaust and Auschwitz were not anomalies but warnings. The ten stages of genocide demonstrate how disregard for dignity and “us versus them” divisions can lead to unimaginable evil, as they did under the Nazis. The hypothetical scenario I described, of a prominent democratic nation descending into genocidal peril, is, in fact, a projection for the United States if current trajectories persist. The events of the last decade, from riots and capitol invasions to assassination attempts and successes, are not isolated but symptomatic of deepening polarization that risks advancing through those stages. Returning to Lauder’s quote: “World silence led to Auschwitz. World indifference led to Auschwitz. World anti-Semitism led to Auschwitz. Do not let this happen again.” We must heed this plea, stop the cycle of hatred, reject dehumanization, and bridge divides before it’s too late. Yet, there is hope: the future is not etched in stone. With collective effort, empathy, and a commitment to human dignity, we can alter our path. There is still time, if we choose to act.

Holidays

Holidays  Girl's Behavior

Girl's Behavior  Guy's Behavior

Guy's Behavior  Flirting

Flirting  Dating

Dating  Relationships

Relationships  Fashion & Beauty

Fashion & Beauty  Health & Fitness

Health & Fitness  Marriage & Weddings

Marriage & Weddings  Shopping & Gifts

Shopping & Gifts  Technology & Internet

Technology & Internet  Break Up & Divorce

Break Up & Divorce  Education & Career

Education & Career  Entertainment & Arts

Entertainment & Arts  Family & Friends

Family & Friends  Food & Beverage

Food & Beverage  Hobbies & Leisure

Hobbies & Leisure  Other

Other  Religion & Spirituality

Religion & Spirituality  Society & Politics

Society & Politics  Sports

Sports  Travel

Travel  Trending & News

Trending & News

Most Helpful Opinions